Understanding the Gregorian Calendar and Its Peculiarities

The Gregorian calendar, widely used across the globe today, has an intriguing history filled with cultural influences, linguistic quirks, and logical inconsistencies. Let us explore its evolution, the reasons for its creation, and the fascinating, albeit peculiar, naming conventions of its months.

Before the Gregorian Calendar

Before the Gregorian calendar, the Julian calendar reigned supreme, introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BCE. The Julian calendar itself was an improvement over earlier Roman calendars, which were lunar-based and had inconsistencies in aligning with the solar year. Over time, the Julian calendar faced a critical flaw: it assumed a year was 365.25 days, slightly longer than the actual solar year (about 365.2425 days). This discrepancy of 11 minutes annually resulted in a gradual drift of calendar dates against astronomical events such as equinoxes.

The Necessity of the Gregorian Calendar

By the 16th century, the drift had accumulated to about ten days, impacting agricultural practices and church schedules, including the timing of Easter. To resolve this issue, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar in 1582. It refined the leap year system, omitting leap years in centuries not divisible by 400. For instance, while 1600 was a leap year, 1700, 1800, and 1900 were not.

Why Some Months Are Named After Kings

The Gregorian calendar’s month names retain Roman roots. July and August, for instance, honor Julius Caesar and Augustus Caesar. These names were not chosen for scientific reasons but rather as a reflection of Roman societal reverence for its leaders. Initially, the months Quintilis and Sextilis were renamed to July and August, disrupting the logical flow of month names.

Why February Has Fewer Days

February’s shorter length—28 days in common years and 29 in leap years—traces back to ancient Roman practices. Initially, the Roman calendar had ten months totaling 304 days, with a winter period unaccounted for. Later reforms added January and February, but February was given fewer days due to superstitions surrounding even numbers being unlucky. It remained the shortest month when the Julian calendar was introduced and carried into the Gregorian calendar.

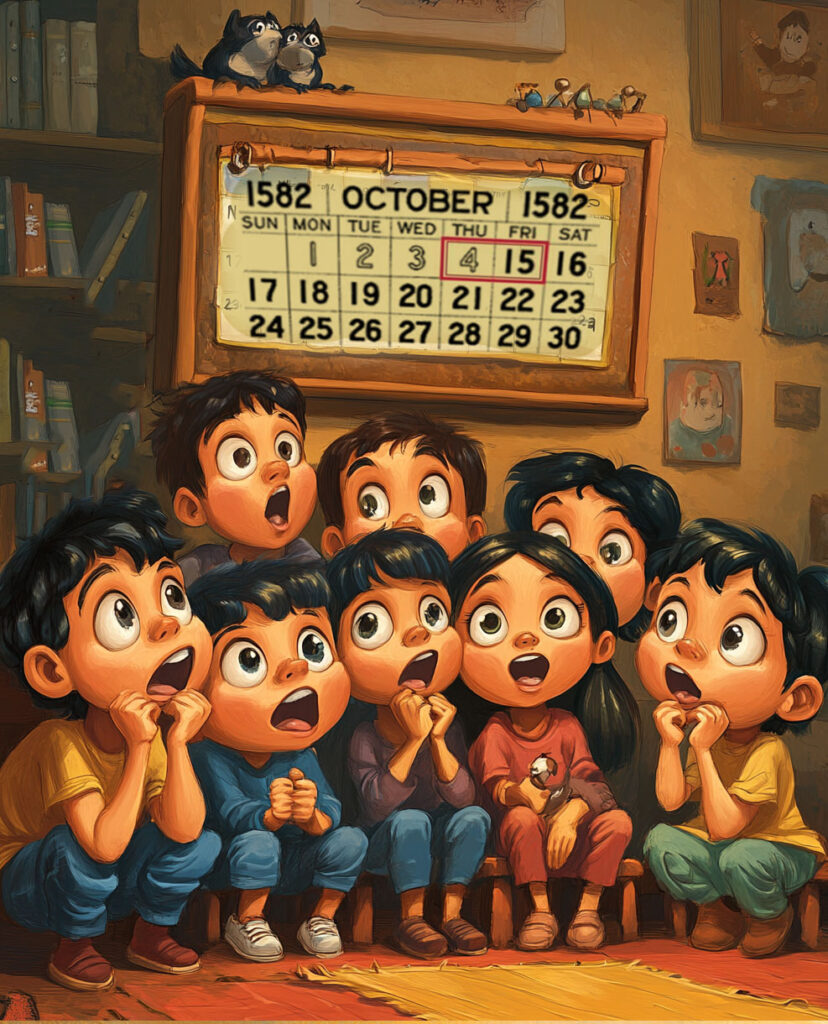

Skipping Days

The introduction of the Gregorian calendar required synchronizing dates with astronomical events. To fix the accumulated drift, ten days were skipped in October 1582, realigning the calendar. This skipping of days was necessary for precision but understandably perplexed people of the time.

The Mismatch Between Month Names and Their Positions

One of the Gregorian calendar’s peculiarities is the mismatch between month names and their numerical positions. This quirk originates from the Roman calendar, which began in March:

September: Derived from the Latin word septem (seven), it is the ninth month.

October: Derived from octo (eight), it is the tenth month.

November: Derived from novem (nine), it is the eleventh month.

December: Derived from decem (ten), it is the twelfth month.

This mismatch occurred because January and February were added later, pushing the original seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth months forward.

The Sanskrit Connection

Interestingly, the Sanskrit names for numbers seamlessly align with these month names:

Saptam (seven) correlates with September.

Ashtam (eight) correlates with October.

Navam (nine) correlates with November.

Dasham (ten) correlates with December.

While Western linguistic traditions borrowed heavily from Greek and Latin, the Sanskrit connections are strikingly logical. The mismatch between month names and their actual positions highlights the lack of scientific reasoning in the Gregorian calendar’s nomenclature. It’s akin to calling fire “water”—a jarring inconsistency for a system so widely used by a modern, scientifically advanced world.

Conclusion

The Gregorian calendar, despite its practical improvements over its predecessors, reflects a tapestry of historical, cultural, and linguistic influences rather than purely scientific rationale. Its enduring use underscores the power of tradition—even when logic and meaning take a backseat. Understanding these quirks offers a glimpse into human history’s fascinating evolution of timekeeping.